A Love Letter: Hunter S. Thompson

- Sammy Castellino

- Mar 12

- 13 min read

Updated: Mar 25

In the years leading up to the making of the cult classic film Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, a young Johnny Depp was sitting in a bar in Woody Creek, Colorado, having some drinks and relaxing, when the front door shot open and yells and clamoring began. Little did he know, this moment was the beginning of a short, yet beautiful friendship. An electric cattle prodder in one hand, and a stun gun in the other, a man shouting emerges from the front entrance of the bar. The man entering with such violence was Hunter Stockton Thompson, a renegade not only in the community, but the country now too, and he was there to meet with Mr. Depp. Hunter Thompson makes his way to the back of the tavern and shakes Johnny’s hand. They share a few drinks, and the conversation is going swimmingly, so much so, that Hunter invites him back to his residence in town; his home base. What happens from here is wildly speculative, but a common thought is that the two wild men took a bit of drugs that evening, Johnny known for indulging, and Mr. Thompson even more so. A couple of decades later, Johnny would recount this experience in an interview with Lawrence Krauss.

Back at Hunter’s home base, the pair are indulging and hanging out, having a good time, when the conversation takes them to his backyard; sprawling fields adjacent to mountains in the distance, Owl Farm’s full beauty comes to fruition. Hunter’s retreat is not just that, it’s a bonding ritual for crazed men such as themselves: shotguns, alcohol, and exploding objects at three in the morning. From here, their friendship only strengthened.

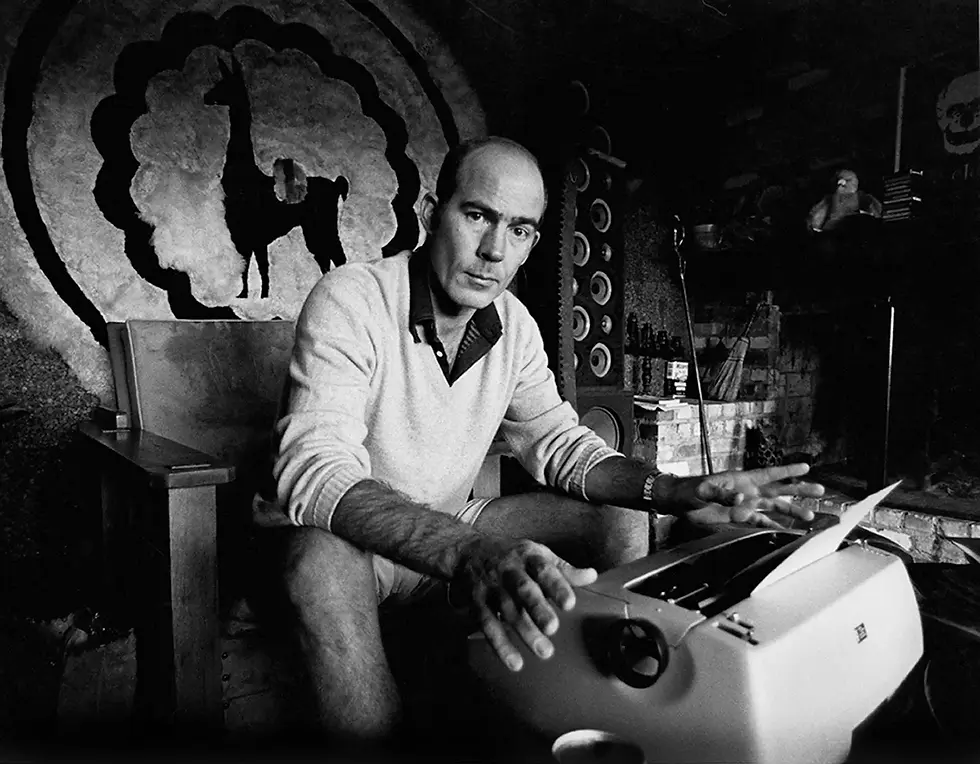

From befriending A-list Hollywood celebrities, to writing some of the most important pieces of literature of the 20th century, Hunter S. Thompson did more than solidify himself in popular culture, he generated an entirely new genre of writing that bridged a long-neglected gap between raw journalism and narrative storytelling, and forged his legacy in the process. His immediate legend was regretfully cut short in February of 2005, when he took his own life, but the aforementioned legacy lives on through his work, as well as many interviews with not only him, but the many people who interacted with him throughout his career and personal life.

Hunter Stockton Thompson was born on July 18th, 1937, to his mother Virginia and his father, Jack. His family was middle class, well-rounded. Virginia worked in town as the local head librarian and Jack worked in public insurance following World War I. While in elementary and junior high schools, Hunter developed an interest and eventual passion for literature and writing in general, and he was motivated by his parents and teachers to pursue it. He took a specific liking to the works of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Jack Kerouac, and Ernest Hemingway, among others, the beat generation clicked with his developing worldviews.

When Hunter was fourteen years old, his father passed away from health complications, and his life would be forever altered from that moment. Being young, impressionable, and distraught at the loss of his father, he began engaging in pranks with the wrong crowds, pranks that would eventually turn criminal. He wasn’t the only one deeply affected by this, his mother, Virginia, turned to alcohol heavily to cope with her husband’s death, leaving Hunter that much more alone. In school, he continued down the writing path, joining the yearbook editor’s club, and taking a passion for covering sports. The trouble he kept getting into outside of school finally came to a head in 1955, when he was removed from the yearbook club for suspected criminal activity. Likely lashing out against the world, this trouble accelerated when shortly thereafter he was found with a friend in a stolen car, and was subsequently arrested and sentenced to sixty days in the county jail. Because of this, the school refused to allow him back to graduate.

Forced to alternative measures, the young Hunter enlisted in the Air Force after being released from jail. After completing basic training in San Antonio, he was transferred to Illinois to study electronics. It was here that he applied to become an aviator, an actual pilot of the planes he spent so much time around, but he was rejected from this too. In 1956, he moved once again, this time to Fort Walton Beach, Florida. It’s here, that he finally found his footing for once, as a sports editor for the football team; he would travel with them around the country, writing about their victories and losses, occasionally doing some work on the side for outside employers as well (which was under the table, as the Air Force did not allow external employment). He didn’t get along with most anybody around him, including his superiors, continuing on his track of distrusting authority, which eventually concluded with him being honorably discharged in 1958.

Now with some actual professional experience under his belt, Hunter travelled to New York City where he did odd jobs for various news outlets such as Time and The Middletown Daily Record, both of which he was fired from for poor behavior. From 1960 to 1965, Thompson travelled everywhere from Puerto Rico to Big Sur, California to edit, write, and report on all sorts of topics, none of which truly scratched the itch he was looking for…

The sails of Hunter’s professional career as a writer and journalist finally caught wind in 1965 when he was hired by Carey McWilliams, an editor at The Nation, to cover and report on the Hells Angels, a notorious motorcycle gang ripping through California. If anything leading up to this is clicking, Hunter had finally found the perfect gig. For those unaware, the Hells Angels were infamous for their violent and absurd tendencies; him being tasked with not only following them but getting a solid grasp on their way of life, so that it could be communicated to the masses in a way they could easily digest. Time would prove that he fit in with this gang. Between ’65 and ’67, Thompson rode with the Angels up and down California as they got into rumbles, disturbed parties, and mayhem in general, recording everything that happened around him, and to him. He established and maintained a relatively positive relationship with the gangs throughout their adventures, right up until the very end. While attending a party with the Angels, Hunter found himself intervening between a violent member assaulting a woman and a dog, which ended with him being brutally beaten himself, just barely saved. He’s been famously reported saying following the event, “only a punk beats his wife and dog.” A few years later, in 1966, Random House published the story as Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs. Its contents disturbed and amazed readers nationwide, quickly gaining traction as one of the most exciting and original pieces of reporting in recent years.

During this period of rising popularity, Thompson became acquainted with many different people from many walks of life, the most important of which, as time would later prove, would be that of Oscar Zeta Acosta, a Chicano lawyer specializing in defending immigrants. This will become important later. What is more important at this particular point in time, was Hunter’s travels to the 1968 Democratic convention. Violent riots took place between anti-war protestors and police and the national guard. His experience covering it was genuinely traumatic, as he was assaulted by police despite his press pass, and witnessed scenes of inhumanity that forever tainted his perception of how one is to treat another. His written report of the event is done under a new pseudonym, Raoul Duke. Duke would later become an icon of his own, but for the time being, he was a shield for Hunter’s traumatic experience at the convention.

It was the spring of 1970 when Hunter S. Thompson’s name would be solidified in major publications all across the nation. Hell’s Angels was being read by more and more people, reviewed by the big outlets, and because of that, he was finally getting the writing opportunities he had always wanted. Where he continues to develop his style, however, is when Scanlon’s Monthly hires him to cover the Kentucky Derby, 1970. With the enlisted help of British artist Ralph Steadman, he writes the piece The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved. The story, supposed to be straight coverage, was instead a collection of personal anecdotes of Hunter and Ralph drunkenly fighting through mobs of equally, if not more intoxicated degenerate gamblers. A satirical, almost comic tone was laced throughout the venture too, making for more of a narrative than anything else; and thus, the Gonzo style of journalism was born.

Hunter was already known for being a degenerate himself of sorts by this point, frequently taking excess quantities of drugs and alcohol, often on the job, to fuel his firsthand experiences. His Gonzo style was notorious for being written while under the influence, and as he rose in popularity, so did his use of substances. This excess led to a paranoia that would follow him for the rest of his life, casually referred to throughout his career as ‘The Fear’, but what most of us nowadays might call anxiety, or borderline PTSD. The 1970s were the rowdiest times for Hunter, beginning with a venture with his close friend and attorney, Oscar Acosta.

Mr. Acosta was well-known in Los Angeles at the time for being an immigrant defense lawyer and activist, as well as being boisterous and confrontational. Given that, the friendship between Thompson and himself seemed inevitable once crossing paths. In the spring of 1971, Hunter was hired by Rolling Stone to cover the death of a local Chicano reporter, Ruben Salazar, at the hands of police during a riot, later titled Strange Rumblings in Aztlan. Given the closeness of the story to Mr. Acosta, the pair teamed up and spent some time in the slums of Los Angeles where the violence had happened. Laced with drugs and alcohol, violent tension all around them, and an always looming deadline, Thompson found himself emotionally and mentally out of shape. Noticing this and feeling it himself, Oscar suggests they get out of town to forget their struggles.

Thus begins the legend of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, a novel by Thompson, yes, but simultaneously a real “vacation” taken by Hunter Thompson and Oscar Acosta to Las Vegas in the middle months of 1971. Hired to cover the Mint 500, a dirt bike race in Vegas, Hunter and his lawyer take a convertible to the desert and waste no time inhaling, snorting, smoking, and drinking their way on the road. What ensues is a collection of mirages and misadventures as the pair stumble their way through Sin City desperately trying to forget the horrors back home. Where the venture takes a turn in the writing, is how Hunter transforms such depravity into a genuinely concrete analysis of the “American Dream” at that time. What should have been nothing more than evidence for criminal activity somehow transformed into one of the most important and popular pieces of American professional literature of the 20th century.

Flash forward a year or two, and Hunter’s name has been permanently cemented in not only pop culture history, but literary. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas spread around the nation like wildfire, his popularity skyrocketing beyond anything he could have ever expected. With the money accumulated from his success, he moved his family and himself to his residence, now home-base, Owl Farm, in Woody Creek, Colorado, just outside of Aspen. It’s here that he would do a majority of his writing. Throughout the following years he would produce works of equal caliber as Vegas, most notably Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72, where he followed Democratic party candidate George McGovern on his quest for the presidency. This work showcased Thompson’s innate understanding of the political process and how his unique and unorthodox approach generated a perspective on our political landscape overall that we would be studying for decades to come. It also detailed an ongoing, and frequently hilarious beef he had with former President Richard Nixon, not unfounded, as the two existed on opposite sides of a number of major issues of the era.

He’d also produce a series of works that serve as collections of letters and articles from various periods of his professional life; these began with The Great Shark Hunt in 1979, Generation of Swine in 1988, Songs of the Doomed in ’90, and continued through the 90s with Better Than Sex in ’94, as well as a few more that were released posthumously. Much later, in 1998, he’d release his one and only fiction novel, The Rum Diary, which was inspired and loosely based on his time spent writing in Puerto Rico in the 50s.

As Thompson’s professional career developed, so did his retreat into his alter-ego and pseudonym, Raoul Duke. Duke, being born out of the traumatic experience at the ’68 Chicago Democratic convention, was already prone to being used as a shield for the discomfort of his fame and frequently psychedelically amplified experiences. Being asked to speak at various colleges and public events, he would show up under the influence of drugs and alcohol, sometimes unintelligible even, and often dressed in goofy attire. The masses assumed this personality to be the real Hunter S. Thompson, though in actuality it was Raoul Duke, a facade for him to hide behind. Nevertheless, when news reports told stories of his work, misadventures, or other, it was not Thompson, but Duke, they truly spoke of. A close celebrity friend of his at the time, one Bill Murray, portrayed him in an adaptation of some of Hunter’s stories entitled Where the Buffalo Roam (1980) further amplifying the disillusioned image of Raoul Duke as Thompson himself.

By the time the late 80s and 90s rolled around, Hunter had pushed his brain to its limits. His writing output decreased exponentially following the release of his letter compilations in 1997 and 2000 (The Proud Highway and Fear and Loathing in America respectively). Alcoholism consumed his life at this point, and unfortunately would until the end of his life. The last major work he was involved in was not his own, but rather Terry Gilliam’s adaptation of his Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas into a major feature film. This was where Johnny Depp and Hunter’s friendship began. Johnny and Hunter, following their initial meeting at Woody Creek, continued to get along so well that the pair would spend a lot of time together shooting guns, reading, and conversing on their shared interests. Before the shooting of Vegas, Depp went as far as to live under the same roof as Thompson for a whole year, in an effort to study and mimic his voice, mannerisms, and lifestyle in general. This proved to be worth said effort, as the film has since become an underground hit, inspiring and introducing people to Thompson’s work to this day.

One of the many consequences of his extended abuse of drugs and alcohol was the alienation of his family. His wife since 1963, Sandy, left him with their son Juan in 1980, since estranged loved ones, whom he’d only see on occasion between his benders. He retained many close friends throughout the years, but given many were famous and busy, and he was eventually relegated to his home base, Owl Farm, in Woody Creek, where he’d end up spending the remainder of his life. While he would continue to write for various outlets, his lack of purpose beyond drinking, and the late-stage effects of alcoholism began manifesting as depression. This clear mental illness continued to get worse in the following years.

On February 20th, 2005, Hunter Stockton Thompson took his own life, with one of his handguns. He wrote a suicide note entitled Football Season is Over that rested on his typewriter nearby. Out of respect for him, I will dictate it now:

“No more games. No more bombs. No more walking. No more fun. No more swimming. 67. That is 17 years past 50. 17 more than I needed or wanted. Boring. I am always bitchy. No fun – for anybody. 67. You are getting Greedy. Act your old age. Relax – This won’t hurt.”

A few months later, on August 20th of the same year, a private funeral for Thompson was held at Owl Farm, his forever home. Knowing he was ready to pass, he had assembled very specific plans for his body and service. It was an expensive endeavor; his widow Anita estimated the total to be somewhere in the ballpark of three million dollars. And Johnny Depp footed the bill. His love for his friend shined through that day, as did many others, almost three hundred people were in attendance, ranging from political figures like John Kerry and George McGovern, to actors like Bill Murray and Jack Nicholson. Following the instructions left, Hunter’s ashes were shot out of a cannon atop a hundred-and-three-foot tower with his infamous Gonzo logo glistening out front, all to the tunes of Spirit in the Sky and his all-time favorite, Bob Dylan’s Mr. Tambourine Man. And with that, his soul went on, but his work and influence remained.

Hunter’s work continues to inspire to this day, and I include myself and my writing passion in that bubble, but truth be told it’s a much larger bubble than just writing. Specifically, Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72 has had lasting implications on the American political process, especially in the context of elections. The references to his analysis and satirical breakdown of the intricacies of the process are littered throughout today’s environment, and you’d be hard pressed getting through any presidential election cycle without at least a subtle reference to his work in that regard.

Moreover, his political involvement in the 1969 race for sheriff in Aspen, Colorado inspired a new movement in American politics altogether. He created his own ticket, with the Gonzo symbol of a red fist clutching a peyote button representing the “Freak Power” party. He lost the election to his conservative opponent, but the flair and motivation of his movement passed on to the coming generations in his grassroots approach to initiating change. I’d be remiss to forget mentioning his trolling abilities during this race, on par with his depraved shenanigans, he shaved his head to be able to refer to his “long-haired opponent”. Throughout his career in reporting on politics, he’d continue using sarcasm and satire to pierce through his adversaries, making it far more common in the mainstream than ever before.

To this day, journalists utilize the Gonzo style in their reporting, sometimes unbeknownst to them. Placing oneself into the story and interacting with the participants is inherently Gonzo, and it’s present everywhere. Every time I turn on the news and watch a story unfolding, I can’t help but notice the influence of Thompson’s work and invented genre; he singlehandedly changed the flow of reporting and journalism in general, and it can be felt every day when reading and watching the mainstream news.

Hunter S. Thompson rode the crest of a high and beautiful wave. His life was tainted with trauma and depravity, but through it all he generated some of the most important pieces of American literature in the 20th century, and continues to inspire writers and journalists to this day. The fact that now twenty years after his passing, there are still countless references, movies, podcasts, etc. revolving around his work or ideas is a testament to his lasting legacy. The most common and favorite comment I hear around the Thompson circles these days is that if he were with us today, he’d be having a field day with our current administrations. He thought Nixon was bad? One can only imagine the searing articles he’d be writing. If his legend accomplishes a single thing, it’ll be being an icon illuminating the hopes and failures of the pursuit of the American Dream in one of the most turbulent times in recent history. I’ll leave you with a rhetorical question, the thought and mystery of what he continues to accomplish to this day: What can we learn from his moralist perspective? Those who criticize his excess might be missing the overarching point of what he was reflecting on society. He was the mirror; we were the horror. Rest in peace, Mr. Thompson, thank you for everything.

Comments